Written by Sarah Elizabeth Goodwin, with support from the DAC team

When I was five years old, I failed the regular hearing test the school gave to all the kindergarteners, and my strange accent and way of speaking suddenly made sense. My parents whisked me away from doctor to doctor until we ended up at the quaint pediatric audiology office at the Connecticut Children’s Medical Center. There, I was promptly diagnosed with moderate to severe hearing loss and fitted with hearing aids. They let me choose the color of my hearing aid molds, and, me being me, I picked a rainbow pattern. Back then I didn’t care how much they stood out; I saw the opportunity to add color to my everyday wear, so naturally, I jumped at the chance. It was a unique look, one that I only ever saw in the mirror, and never in the world around me.

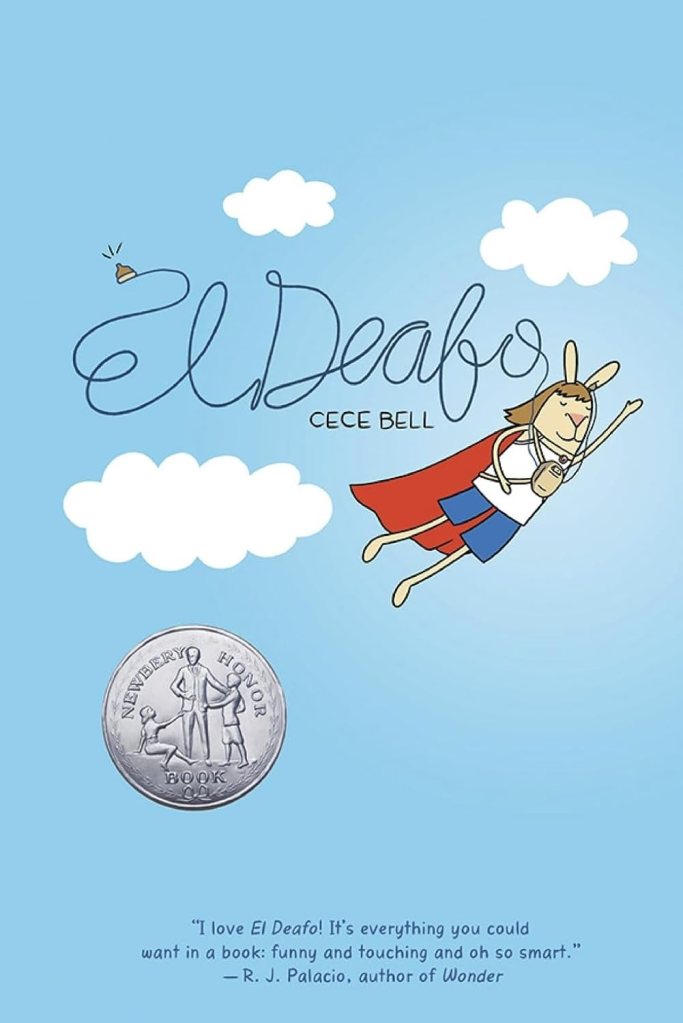

El Deafo by Cece Bell was one of those books that I would have benefited from having on my childhood bookshelf. Unfortunately, it wasn’t published until 2014, and at that point elementary school was but a distant memory. Nevertheless, reading it now is still a lovely experience. In the main character Cece, I see a lot of myself. Despite her story taking place in the 1970s, I see a lot of my experiences as a hard of hearing 2000s kid. Even though our levels of hearing ability are different, she is incredibly relatable. We have a lot in common. Cece had wires going from her Phonic Ear to her aids. Those wires weren’t needed by the early 2000s, when I started wearing hearing aids, but until second grade or so, my hearing aids were clipped to my shirt via these little cords, so that if they fell out of my ears, they wouldn’t be lost. It was a similar look to Cece’s aids, and it stood out just as much.

Being a kid with hearing loss was incredibly lonely at times. Cece describes the feeling perfectly. She felt like she was stuck in a bubble, on display where people just stared at her and never interacted with her (45-47). With the cords as a part of my daily outfit, I attracted a lot of eyes, too. Even when I was finally trusted to walk around without them, my rainbow molds still brought a lot of questions from curious classmates. I hated the attention so much that when it was time to get new aids right before middle school, I got molds that matched my skin tone, rendering them practically invisible.

Making my disability invisible did make me stand out less, but it also had the effect of making social interactions harder. Cece represents what it’s like to be in the general din of conversation so well in the book. On the first panel of page 36, Cece and her siblings are meeting kids from their new neighborhood, and every conversation that is happening around her is unintelligible. She hears words but can’t make sense of them because most consonants are not in her range of hearing. As she directly states later in the book when another girl insists on blasting the TV, “I can hear it! I just can’t understand it” (92). This is a perfect description of my experience. When people around me speak, they tend to mumble and run their words together, many important sounds getting lost in the process. My whole life is basically a half finished game of hangman; I can’t get any more letters, and I must try to guess the word or phrase from the few clues that I have. People tend to get impatient if they have to repeat themselves, or wait too long for me to unscramble the mess of sounds into words, so most conversations end with, “Nevermind, I’ll tell you later,” a promise no one ever keeps.

Another issue both Cece and I faced was the fact that when someone meets us and learns about our hearing loss, we are usually the first deaf/hard of hearing person that person has ever met. Cece spent elementary and middle school never meeting another child like her. When she saw someone on TV with a Phonic Ear, she was so amazed to see someone like her. Even when another character on TV called the deaf character a “Deafo,” it stuck with Cece. Although the name was supposed to be negative, Cece embraced it anyway, thus creating her character of the superhero El Deafo (81).

I also never met another person like me, not until I was well into high school. As a result, I never really felt like I was “normal.” I never saw people like me in school or on TV or in books. On the rare occasion that I did see myself in a story, my English teachers would have my classes break down the symbolic meaning of the character’s disability. To them, “disability becomes metaphorical, something that must be explained, understood, and ultimately overcome” (McCorbin 2016). It could never just… be. It made it hard to enjoy characters like me because it was always in the back of my mind that the story treated their disability like a personal flaw.

It also reminds me of how as a child, I was always known as “the girl with hearing aids” or “the deaf girl.” My identity was boiled down to one thing about me I couldn’t change. I saw something similar in Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral,” where the narrator referred to Robert only as “the blind man.” His name was only used in moments that “humanized” him, such as the narrator thinking about the loss of Robert’s wife and what he must have gone through (Carver 4). Cece experienced the same thing in El Deafo, where many of her classmates did not see past the Phonic Ear or her hearing aids. She was known as “the deaf girl,” and it was quite isolating.

I think that feeling of isolation is the reason why Cece Bell wrote this book. She wanted to share her experience as a deaf child, and perhaps make other children like her feel less alone. I know that I as a child would’ve found great comfort in seeing myself on the page, portrayed in a relatable and positive manner. I didn’t have a lot of that as a kid. I had a couple short picture books with deaf and hard of hearing characters, and that was all. A full length novel would’ve been amazing to have.

Even though I didn’t have this book as a child, deaf children of today all over the country will likely find comfort and a sense of belonging in Cece’s story, which is why it is so important for stories like this to be told. With many disabled folks starting to share their experiences, disability becomes more mainstream and normalized, which I think will make the next generation feel more connected and comfortable in their skin.

Works Cited

Bell, Cece, and David Lasky. El Deafo. Amulet Books, 2014.

Carver, Raymond. Cathedral: Raymond Carver. Wadsworth, 1981.

McCobin, Julianne. “Disability and Its Metaphors,” 2016, https://disability.virginia.edu/2016/03/14/disability-and-its-metaphors/