Presentation by Kelly Coons, with support from the DAC team

Creator’s Statement: This video, created for an annotation assignment in ENGL / WGSS 6750 – Doing Disability Studies in the Humanities, aims to distill 18 models of disability through the lens of a question and answers segment. There is a dash of parody targeted at the depth of questions that are nonetheless expected to be answered so quickly – recreating this in the realm of speed dating. The prompts I crafted, I intentionally designed to be answerable with a simple “yes” or “no”; still, indeed, but ones that people, in practice, answer in a (usually-impenetrable) word wall. Through this process, I found that paradigms that often appear to be opposites, at their core, can prove to be occupied with similar goals.

This project is not designed to be a study guide, but the jumping-off point for a conversation about questions that cannot be answered with a yes or no: questions like, “How do the core assumptions about we make about disability change (or not) over time and/or depending on the situation?”, “Is there an ‘ideal’ way we should frame disability and who gets to decide what that goal is?”, and “How does the intersecting identities of individuals affect how they view disability (both in themselves and/or in others)?” The questions in this piece are framed as binary (and, later on, ternary), but, in reality, for most models, you can argue, with textual evidence, for the “other side” as well.

Slideshow Presentation:

Three-Minute Long Video:

YouTube Video Conversation ft. Brenda Brueggemann (With Captions): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=siUB_Ha85Bg

Transcript of YouTube Video Conversation ft. Brenda Brueggemann (With Key Points Bolded):

Transcript edited by Hannah Dang, with support from the DAC team

Caption: The following is a transcript of a conversation between BRENDA, the leader of the Disability Access Collective blog, and KELLY, the author of the submission, “18 Models of Disability,” about the origins, process, and tonality of the submission.

BRENDA: So we’re here on the… October… What is it, Kelly? It’s October..?

KELLY: Fourth.

BRENDA: It’s October 4th, 2023, and I’m talking with Kelly Coons, and we’re talking about a piece for the DAC Blog (Disability and Access Collective Blog) that she’s contributed, and we’re going to do king of an interview about the origins and process and elements of the project.

BRENDA: And… So you wanna say hi, Kelly? *waves*

KELLY: Hi! *waves and smiles*

BRENDA: So, Kelly, first tell me about like this project- Like maybe you can do a quick audio description of it.

KELLY: Yeah.

BRENDA: For someone who can’t necessarily see it very well.

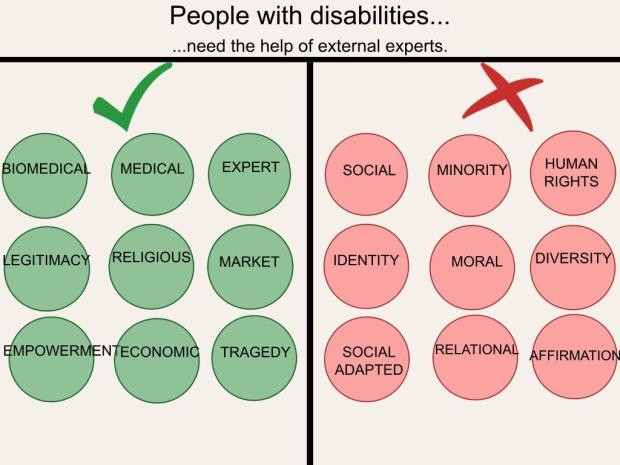

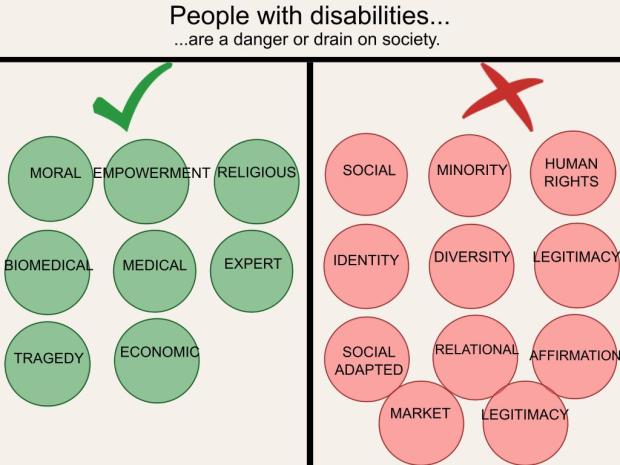

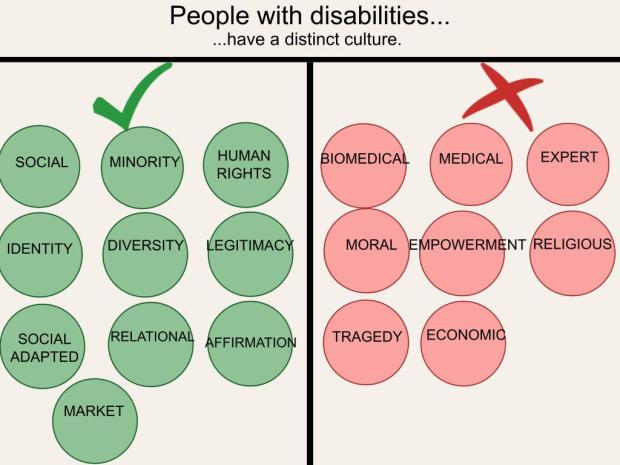

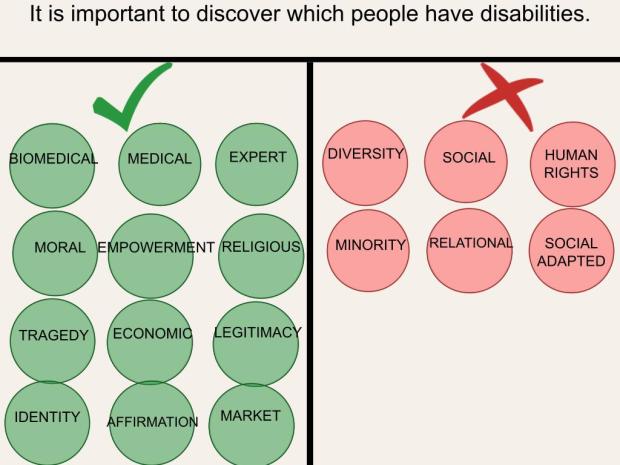

KELLY: Yeah, so… I was looking at an article. I think it was from, like, Disability World.net. I forget- A lot of websites that had that similar sort of, like, “Disability Blank” name, so I’m, like, which one is it from? But I’m pretty sure it’s Disability World. And it was kind of trying to provide some plain-text explanations of 18 different models of disability. So 18 different ways of framing disability. Common ways as, like, disability as like a health issue. As embodied. Disability as existing because of the environment and being separate from the body. Disability as some sort of moral marker. Those are kind of the Big 3 there.

BRENDA: Okay. Excellent. Yeah.

KELLY: But yeah, but then 18. But, like, within those big 3, variations within them that equaled, um, 18.

BRENDA: Yeah.

KELLY: And I was struck that even though the intent was for it to still be plain text, especially for ones that were in the same “family,” it was kind of hard to parse what the differences were. Like there’s an economic model of disability and a market model of disability like..?

BRENDA: Yeah.

KELLY: Those seem pretty same to me! Yeah.

BRENDA: Excellent. So you caught on to even like I offered the text for the class. I’ve used it for the undergrad class too because when you Google in “models of disability”, you know, I stop looking after 3 screens—3 full screens. You know, all the sites that have models, and for the most part it was, you know, the medical and the social model, and there might have been one other one. But not very ritual buff. And when I ran into that one, I selected it because I’ll say on the first face of it, it seemed cool because it was very complex because there were 18 models like-

KELLY: Hmm.

BRENDA: But then I must say that I shared the same interpretation that you did, then it all gets kind of oversimplified. You might have 18 and like I don’t know- My students said last year in the undergrad class, “Well, how do you tell these apart?” And we tried it with various texts, like, to read them. Through the various models, you’d spend more time trying to, you know, parse out which was its best model than probably make any sense. So.

KELLY: Hmm. Although I was struck by in the text—kind of this progenitor text that I guess I, you know, helped birth this new version of it into the world. I have- Here’s a midwifery metaphor. Like, and a lot of just going out into the wild, wild West of Google, um, a lot of times you immediately counter- encounter, like, before you even finished reading a description of what a model of disability is—whether it’s social, whether it’s model- medical (it’s really only those two out in the wild)—you immediately capture the “This is good because-” or “This is bad because-” and in this text, it was left open. I mean, even the religious model of disability that said, like, people with disabilities are punished by a divine deity. I think most people would say that’s bad, but the text didn’t say that!

BRENDA: Yeah. Yeah, that’s what I said. It’s more complex. So I like to use it because it kind of brings up some some of the vexations that I talk about that are always around the subject of disability. Oh, that was great. So you decided kind of- I would say what you did was like even complexified even more.

KELLY: Well, that’s how conversation works. *chuckles*

BRENDA: Yeah, kind of! Trying to parse out certain domains- So now then the process. So. How did you decide, like, to use the circle that- I mean tell me about the process of some decisions you made to turn your annotation about this piece into the frame that you did?

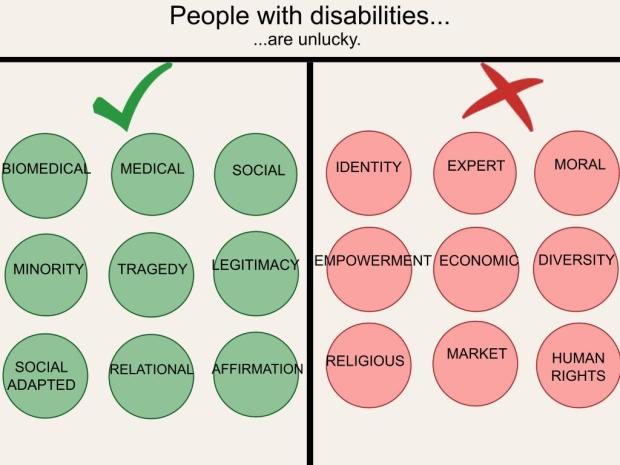

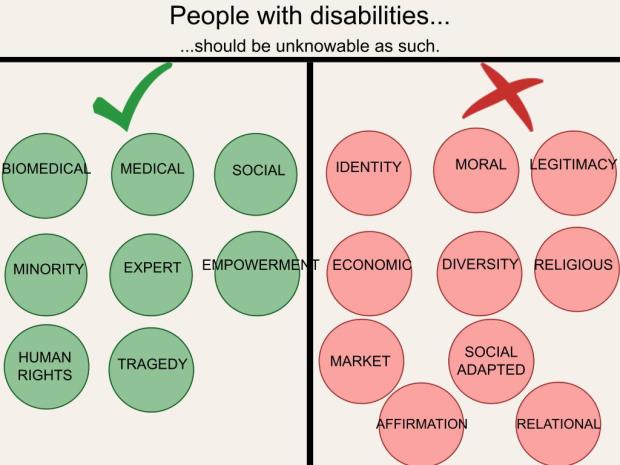

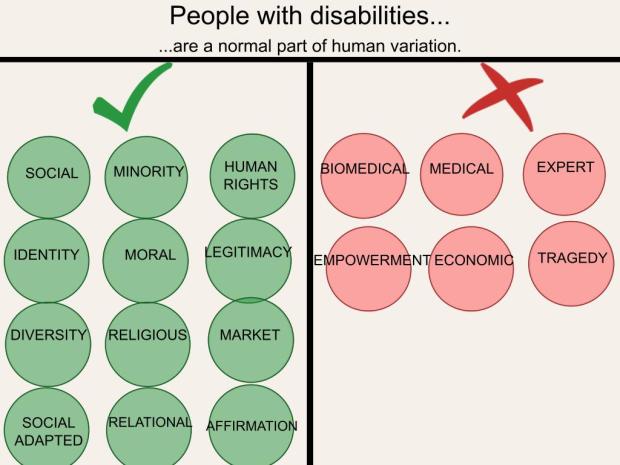

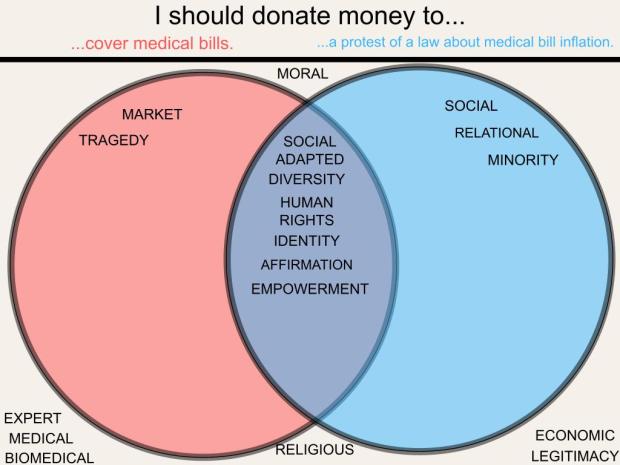

KELLY: One of my favorite kind of rhetorical turns when I’m engaging with a text is to turn a statement into a question. Because a statement presupposes an answer, and I was trying to reverse engineer what was the question that was asked. So with the example of the economic model versus the market model, the economic model, it seemed was older, so it’s like, okay, what was the question that caused this spin-off into the market? And a bit of a spoiler for the annotation itself—but, for me, the big difference between the economic model and the market model seemed to be the question of like, “Is- Are people with disabilities a demographic worth marketing to? Like, what is their spending power?” Because the economic model says they are just a drain on the economy.

The market model, meanwhile, has the very, um, liberal but not leftist opinion of, “Oh, but you know disabled money is the same money as everyone else! And sometimes they need to even buy extra things!” That to me seems like the differentiation of the market and economic model. So I was like, well, if it works really well for kind of trying to separate the parents from the children, so to say, I was like, what if I just did that for all of them? That was my idea behind asking questions. And then when I went around making the questions, I was thinking about, “Well, I found this like funny little graphic.” That was like, you know, anime blush. And I was like, “I’d love to use this!” And I was like, “What if it’s a dating show?” But, like, a strange dating show. You know what you like have to get- I mean, all of them are strange, but like, in the way that, like, “I am going to ask you a deep, cutting question that you must answer as a yes or no.” But nobody actually does answer yes or no. Like, if you ask someone who is trying to sell, let’s say like, decals for wheelchairs, and you ask, like, “Do you think people with disabilities are a drain on the economy?” They’re probably not gonna answer yes or no, even though they certainly have an opinion. They’re gonna kind of answer you with a word wall that you can’t quite penetrate.

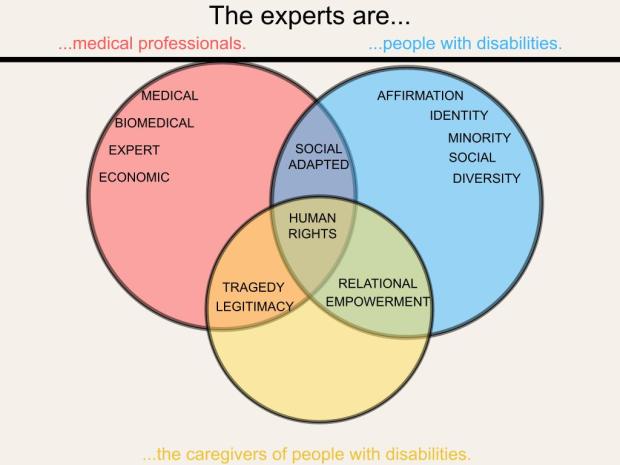

So I wanted to get to the point of I want to give them yes or no, recognizing that they might be different ways, particularly for like, I’m gonna call it the second and third generation models. So our 3 medical, social and moral, are kind of our first generation. Those ones I think were pretty easy to parse. But then we start getting the second generation—like I would call economic, a version of moral because the idea is disability makes you inherently draining. I don’t think most proponents of the economic model would say that makes you evil. But it doesn’t make you useful, which makes you bad. Not evil. But a difference. When we start getting especially to those second and third generation models, I was thinking about like, well, “And these are the models that. Most people. Most people want to present as more enlightened. And how do you present yourself as enlightened in a Western, capitalist, even like an academic space in particular? More words. More words is the answer!” So I wanted to kind of strip that down and say, “No, you get one word. Yes or no?” You get one..! *laughs*

BRENDA: Yeah, oh that was excellent! That was a fabulous explanation! That I mean I felt like I kind of understand what understood what you were doing already, but how that was even richer. I wrote down, I really love that “Turn of statement into a question.” That will probably be coming back to you as a class activity.

KELLY: *laughs*

BRENDA: *laughs*

KELLY: I still have one more annotation for this class, so I’m like, maybe I’ll do that as a turn. I was also thinking about the idea of just Mystery Science Theater style commentary. But in so many of my other classes, I’m doing kind of, like, that deep reading annotation style. And I’m like, hmm, hmm. When does it just become fatiguing? This is- This is something not like I’ve been doing in my other classes. So I’m like, “Yes, let’s use Canva.”

BRENDA: Remember then like the category, you know, on each slides there’s like a different set of yes/no question but. Do you remember any examples of how that process like how, you came up with a couple of the categories?

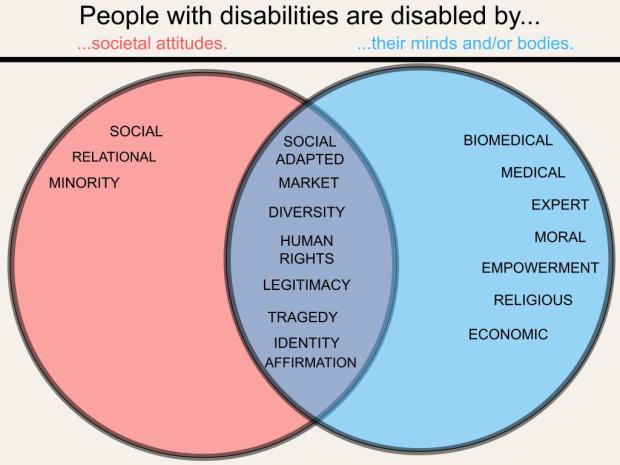

KELLY: Well, I initially did… And I have the… This is the power of doing this over Zoom. I have my Zoom on my left side and then my reading on the right side. So I can actually just physically look and see. Initially I just did the yes/no. But you can see at the end there are two that have a two-way Venn diagram. So it’s not yes/no, but it’s still a binary answer. So I was thinking about. For the first one I came up with. It was people with disabilities are disabled by… societal attitudes or their bodies and/or minds? And that was kind of the original two you find on the internet, which is the social model (People with disabilities are disabled- There’s nothing in inherent to, for instance, being a wheelchair user that makes you disabled. What makes you disabled is that there aren’t ramps.) meanwhile, the medical model is there is something diagnosable (and it’s often diagnosed by someone who does not have a bodymind like you) that diagnoseable in your body and/or mind (and often those types of disabilities come hand in hand). Some of us- The chicken or the egg. Like, do you have depression? Higher rates of depression, if you’re a wheelchair user, because you can’t access spaces if you’re a wheelchair user because you can’t access spaces or is there something inherent to… “Lack of mobility,” shall we say, that also creates “lack of flexibility” in the mind—and this is very quickly where medical knowledge just becomes very, like, purple prosy and poetic, and I also wanted to kind of pull that together, but also a Venn diagram doesn’t just the allow for yes/no, it also allows for that middle space.

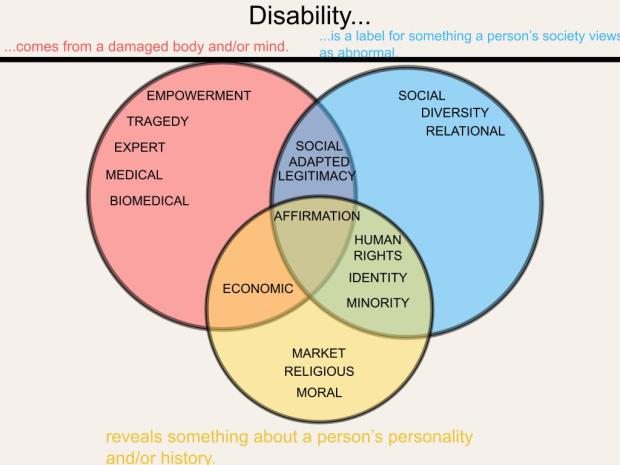

So very quickly I found the social-adapted model which is basically, “Yes, people with disabilities are disabled by societal attitudes and their bodies and/or minds.” So, for instance, if you are a wheelchair user, even if everywhere you go as a ramp, you might have chronic pain that is completely separate from the ramp. And then I was like, “Hang on, what’s the level up here from having a two-way Venn diagram?” Because initially my plan was to do an 18-way Venn diagram. No. I tried. It did not work. But. What does work is a three-way Venn diagram! And this is actually something- I also am a First-Year Writing instructor at UConn, and one of my class activities involves the three-way Venn diagram. I see you making a face.

BRENDA: Excellent. Yeah, because, well, you know, the piece for reading class. Bonnie, Rumi, on the Circle Wars and the typical Autistic essay and when she wrote on this rant against circles and Venn diagrams in general. And I thought that you captured some of that because especially when you when you kept doing them and putting the circles you could begin to see the little bit of nonsense.

KELLY: Especially when you get in the middle of the three. Like the affirmation model is somehow in the perfect center of “Disability dot dot dot.”

BRENDA: Yes. Yeah. So that was what happened to that like kinda like tone, so it was. I mean, how would you describe the tone? I would say I see the seriousness of it. And taking it on thoughtfully, but also the snark, the irony.

KELLY: I think, see, I’m looking at the PowerPoint version I have right now just so I don’t have to keep pausing and if there’s any like audio bleed. I think the PowerPoint version is read very differently from the video version. Even if you do not have the sound on, just the kind of like almost like bouncy movement of Canva’s almost default movement makes it I think have a lighter tone than the flatness of a PowerPoint slide.

BRENDA: Hmm. Yeah, yeah, because PowerPoint’s code is being “educational” “informational” to- not necessarily entertainment. I mean, they already code rhetorically in certain ways from-

KELLY: Oh, I try. I hang out in that animations tab. It might not be successful, but I do try.

BRENDA: Yeah, yeah. Well, okay, and so that I think that’s my final question there is that there was this PowerPoint but then there’s also a video and there was a 1-minute version of the video and then there’s a longer minute version of the video. Talk to me a little bit about the different kinds of talk or choices or the doing of those or impacted reasons for those different versions.

KELLY: Yeah, so the 1 min video came first, because initially I was not thinking about-

[CHARLIE, one of BRENDA’s cats, jumps into frame.]

KELLY: Baby kitty!

BRENDA: Okay. Charlie, Charlie came to say hi.

KELLY: Oh, Charlie. So sweet. Charlie, you’re gonna be famous! You’re gonna be on the DAC blog!

BRENDA: That’s right. Well, he’s certainly been in DAC Blog meetings before.

KELLY: Yeah, he’s been at DSQ meetings too.

BRENDA: He literally lays on top of my arm, the one arm here and I can’t do anything with the arm. This one.

KELLY: Baby. Disability is made by cats, don’t you know?

BRENDA: Exactly.

[Both laugh.]

KELLY: That’s like the April Fools version. But, the one-

BRENDA: Instead of being thoroughly incapacitated, I’m furrily incapacitated.

KELLY: Yes. Yes! So the 1-minute version came first because I was initially just not thinking about the dimensionality of the slides. Also, I spent so much time on those slides. Coming times I had to copy and paste that anime blush on the first page, I’d already memorized the 18 by the time I made it to the next slide. So I just was thinking, “Oh, you can just read it. You can just see it.” And it’s like, “Well, no, those are kind of like burned into your brain, Kelly.” Like the way that if you pause on a screen too long, your television will kind of burn in that image. That’s what had happened to me. So it wasn’t until I handed in the first, minute version, 1-minute version that you, Brenda, were like, “Hey, this is fast.” I was also just thinking about like- I’ve done a couple of like Instagram reels when I was promoting, my own book and Instagram reels is like the maximum length is one minute. IGTV is for longer. I’m not even sure if IGTV exists anymore. But like the idea that one-minute threshold gets you at a certain engagement bar and then anything longer than that goes further. So. I guess somewhat unconsciously I was thinking about like, “One minute! One minute to make an impact!” So I think the final version is like 3 times as long hang on each slide. And obviously there’s the ability to pause. But I don’t think that’s an excuse, but.

BRENDA: Yeah, excellent. And again, you, that was very well put. So the sort of rhetorical choices, the impact on audience and interaction that happened across those 3 frames is very different in connection with it. Yeah, because you know even on PowerPoint, I you could start skipping back if you want to, but to get the-

KELLY: The classic move of putting a like a a lecture on like 2 times speed. Unfortunately, you can’t do that in real life.

BRENDA: Yeah.

KELLY: Or the alternative of turning it like 0.75 speed. Once you start getting slower than that, it just stops sounding like human words. But, 0 point 7 5 times like- Probably 0 point 7 5 on me is probably pretty good.

BRENDA: Yeah. So thank you for pointing that out. I thought access, but it can be counter-access also. But I thought by offering it in multiple ways, you offered again multiple ways to access. And then engage the video for different people. I know, for example. a couple of my blind academic friends are driven to tears by all the required university, like, compliance videos that we have to do every and they make them, of course, that you cannot speed them up or skip past them and you know these are people who listen to the sound of words at 3 times the speed. I mean it just absolutely. Is just soap.

KELLY: And if you try to click away, like it just cuts off. Or you can’t actually pause until you’ve watched the whole thing. ‘Cause sometimes I wanna pause and like take a screenshot, especially if there’s like a little like flowchart and then it’s like, oh, I missed the screenshot.

BRENDA: Yeah, I’ve not ever tried that, but that’s probably actually true also. And so and they kind of like necessary but it really creates a kind of access barrier for them, that pain of listening to something so slow. I know one friend says she can’t absorb it because it’s just too slow. Like listening to a radio at 70 at the 7- I mean that radio a record that’s supposed to be at 78 rpm right at 33.

KELLY: I think about the classic example of like a video game that’s supposed to run at 60 frames per second frame-dropping so hard that it like “turns into a PowerPoint.”

BRENDA: Yeah.

KELLY: But you’re just like, “Oh, this isn’t the game anymore.” Like I’m just watching a series of silent images. Also known as Modern Pokemon. As a Pokemon fan, I can say that.

BRENDA: Okay, good. Anything else that you wanna say about?

KELLY: No, I’m just admiring Charlie.

BRENDA: Yeah. He, wants this wet food, that’s what he wants. So, and he’s reminding me.

KELLY: Oh, and he can’t just knock that down himself.

BRENDA: He’s reminding me that I haven’t done that yet.

KELLY: Oh, they’re so helpful. What would we do without cats?

BRENDA: Well, in October, I really, try to push and train for a little bit later because we’re gonna go through the time change. Then they don’t do that. No. So I work it in the other direction. That’s our driver. I mean, I’ll be in a department meeting, you know, till late in the afternoon and they’re driving me nuts. Well, this is on the video now. Okay, and I left the screen open, so there’s a bug in here now. I left the patio door open a bit this afternoon-

KELLY: What are cats for? Get on that, Charlie!

BRENDA: He was watching that for sure. I don’t know what kind of bug it was. On those notes, I’ll let us go. This will download and then I’ll put it in the Google folder and share it with you, okay? Alright, good night.

KELLY: Good night! *waves*