Presentation by Mary-Katherine Cormier, a UConn Student, with support from the DAC team

A Note Sheet to Accompany the PowerPoint

Introduction

- Etiology of Deafness

- Middle- or inner-ear structural differences

- Etiology of Autism

- Atypical patterns of synaptic pruning

- Primarily in frontal lobe of the brain

- Two very different etiologies with a similar presentation

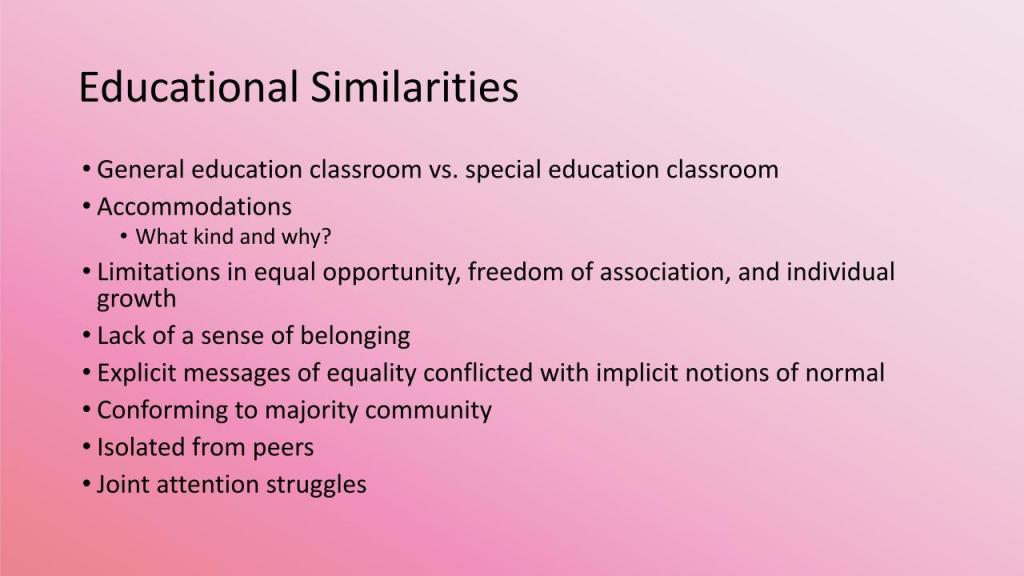

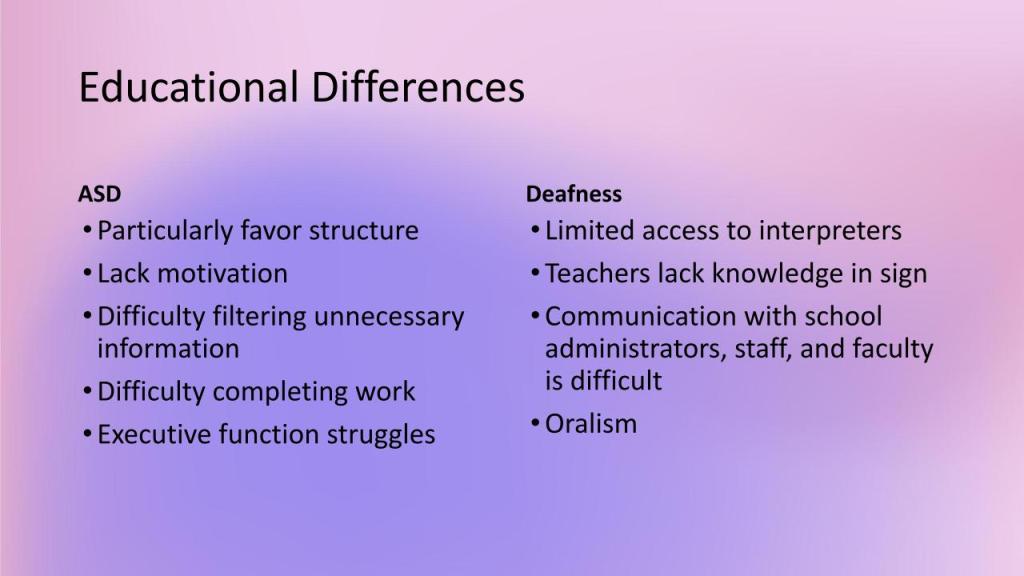

Education

- Deaf

- Accommodations, but only to the extent that it doesn’t impact non-deaf peers

- Explicit message of equality conflicting with implicit notions of normal

- Very limited/no ASL knowledge by teachers

- Limited access to an interpreter fluent in ASL

- Non-deaf students can communicate directly with student administration, staff, and faculty; deaf students need to use an interpreter or attempt to write/speak

- Limited/no ASL classes offered

- On three axes- equal opportunity, freedom of association, and individual growth- non-deaf students received this and more in their education, but not deaf students

- Deaf children who act hearing in mainstreaming settings may have a social advantage over those deaf students who do not, for they tend to become isolated from their non-deaf peers

- Deaf students didn’t advocate for themselves, denied communicative needs, trying to integrate into surrounding non-deaf community

- Clear speech as high priority (oralism), speech lessons

- When the deaf students passed for non-deaf, when they spoke and complied with the mores of the fifth-grade cultural group, they were welcomed, noticed and accepted

- May spend time in a separate “resource room” apart from “general education” classroom; deaf students placed together in resource room and in same gen edu room

- Being carted around the school, between multiple classrooms, not feeling a sense of belonging in any classroom

- >70% of deaf children attend mainstreamed schools

- ~1% of school age children are deaf, are always a minority despite merging efforts

- Unchanging special education classroom structure

- Autistic

- Echolalia- associated with learning difficulty and poor school performance

- May be in a general education classroom or may be in a special education classroom

- More likely to be moved to a special education classroom, including those with average and above-average IQs

- Respond well to structure

- Lack motivation, have difficulty engaging and filtering unnecessary information, have trouble successfully completing work, demonstrate cognitive rigidity, and struggle with executive functioning

- Strength in visual processing

- Deficits in joint attention

Language Acquisition

- Deaf

- English, not ASL, being used in classroom settings

- Spoken English promoted

- 80% of deaf children get cochlear implants; most do not experience success with the implant and are also NOT exposed to sign

- Success=weakness in language competence, ease in which they communicate in a speech-only environment

- Signed languages develop the brain in the same ways as spoken languages do, and doctors often recommend or insist that the family of a deaf child keep said deaf child away from signed languages, actively depriving them of language and potentially missing integral neurodevelopmental periods (critical periods)

- Children who miss this critical period run the risk of not acquiring native fluency in any language

- Cognitive activities that rely upon language acquisition are then subsequently disrupted

- Math, organization of memory

- Deprivation diminishes educational and career possibilities- lack of literacy limits these

- Autistic

- Strengths and weaknesses as compared to neurotypical peers

- Impaired pragmatic abilities- difficulties in responding to questions and sharing and requesting information, narrative productions

- Grammatical and semantic components of language are less impaired overall

- Use limited range of morphological and syntactic forms in their spontaneous speech

- Word meanings are not as detailed and well integrated across lexical domains

- Children’s progression of grammatical development is not impaired

- Nonverbal autistic people use augmentative and assistive technology or sign

- Echolalia- repetition of words or phrases, in 75% of autistic children

- Language delays

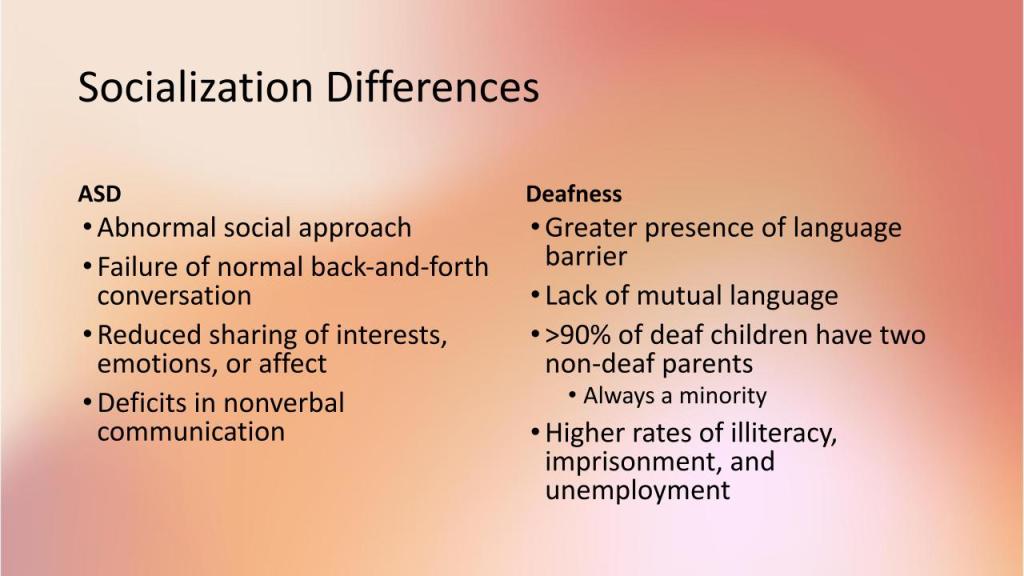

Socialization

- Deaf

- Very few peers in school setting know sign

- Lack of a mutual language creates barriers in making friends

- May be in separate room from school peers, lack of sense of belonging

- Always a minority

- >90% of all deaf children have two non-deaf parents

- Traditional parent/child communication venues are generally not available to deaf infants, usually are addressed through spoken language

- Majority culture defines the concept of ‘normal’

- In playground play, Deaf children are more likely to engage in nonsocial ways, which has been linked to less emotional understanding, internalizing symptoms, lack of social skills, and peer rejection

- Deaf children are less successful in initiating and maintaining social interactions with their peers, interactions with others are characteristically shorter, and they are less frequently invited or allowed to join in play

- Linguistic deprivation leads to psychosocial problems- inability to express oneself fully and to easily understand others completely

- Higher rate of illiteracy, imprisonment, and unemployment

- Illiteracy strongly correlates with high unemployment, poverty, and poor health

- Those who cannot communicate effectively are often abused

- Autistic

- Echolalia can impair social interactions and learning, a barrier to forming and maintaining social relationships

- Aggression, anxiety, depression; caregiver stress and family conflict; peer victimization; social isolation from bullying and non-acceptance

- Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts

- Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions

- Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication

- Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers.

- Echolalia can impair social interactions and learning, a barrier to forming and maintaining social relationships

WORKS CITED

Jean T. Slobodzian (2011) A cross‐cultural study: deaf students in a public mainstream school setting, International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15:6, 649-666, DOI: 10.1080/13603110903289982

Da Silva, B. M. S., Rieffe, C., Frijns, J. H. M., Sousa, H., Monteiro, L., & Veiga, G. (2022). Being Deaf in Mainstream Schools: The Effect of a Hearing Loss in Children’s Playground Behaviors. Children (Basel, Switzerland), 9(7), 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9071091

Humphries, T., Kushalnagar, P., Mathur, G., Napoli, D. J., Padden, C., Rathmann, C., & Smith, S. R. (2012). Language acquisition for deaf children: Reducing the harms of zero tolerance to the use of alternative approaches. Harm reduction journal, 9, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-9-16

Swensen, L.D., Kelley, E., Fein, D. and Naigles, L.R. (2007), Processes of Language Acquisition in Children With Autism: Evidence from Preferential Looking. Child Development, 78: 542-557. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01022.x

Patra KP, De Jesus O. Echolalia. [Updated 2023 Feb 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565908/

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013

Kathleen A. Flannery, Robert Wisner-Carlson. Autism and Education. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, Volume 43, Issue 4, 2020, Pages 647-671, ISSN 0193-953X, ISBN 9780323836067, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2020.08.004