Written by Elisa Shaholli with support from the DAC team

When it comes to my diagnosis with type one diabetes, as much as I hate to admit it, I tried to embrace the dreaded “Supercrip” archetype growing up: yes, I have diabetes. And? Why should that be a precursor to any action I take? I don’t advocate, nor will I ever, that just because you have diabetes (or really any disability or medical condition), that you should be accepting of doors that people try to close on you.

Through this post, I hope to dwell on my own realization that no one is invincible, and that includes me, even though I don’t always want to admit it (who does?). As much as the “Supercrip” archetype is encouraged by, and for, those of us with disabilities, it’s just as crucial that we embrace self care and prioritize ourselves.

These past few days I’ve been out and about in Tokyo, Japan, specifically in Shinjuku. It’s a wonderful city with a rich culture, tasty food, and a beautiful language. It’s been the location where I’ve enjoyed some of my favorite moments, but it’s also the place where I realized that invincibility is nonexistent for me, and how crucial psychological health and decision-making is for those of us with disabilities that don’t primarily surround the psychological state.

As a visiting student in Shinjuku, Japan, I went to sleep a few days ago after following my usual routine: I checked my blood sugar on my insulin pump and noticed the insulin was running low. There were around thirty units left on my pump, but I didn’t think much of it. I could change it in the morning. I had eaten a late “dinner” made up of convenience store foods— bread, cucumber, some mochi and other Japanese convenience store snacks. Everything was going well.

Fast forward a few hours when I suddenly wake up, look at my insulin pump, and discover that for the past two hours, my blood sugar was so high that the number was not registering on my insulin pump anymore. Instead, a blaring yellow “HIGH” was plastered on the screen. I immediately started administering insulin through the pump. No blood sugar changes occurred as the HIGH was still on the screen, and my anxiety slowly increased. I changed the insulin pump cartridge set with new insulin, and started distributing more insulin. I thought that maybe the prior insulin distributions did not go through, since there was a low amount of insulin in the prior cartridge. All I could think was that I’d done this hundreds of times before. It would take a while for my blood glucose to go down anyways. I could go back to sleep.

Wrong.

My blood glucose number started to descend. Every five minutes when the blood glucose number updated on my pump felt like a ticking time bomb. Although I wanted my number to stop being so high, I didn’t expect the number to start decreasing as quickly as it did. With the speed the numbers decreased, I realized the amount of insulin I had given might have been exorbitant. I gave insulin, expecting the number to take a while to decrease, so the units of insulin distributed seemed fine at the time. As the number kept going down though, I suddenly wished I hadn’t given so much.

First the number would decrease by ten points.. then fifteen… then another ten…. Where anxiety hit me over high blood glucose prior, panic now struck on lows. My mind immediately went to the worst possible situation: What if I need to go to the hospital? I only knew basic Japanese. I couldn’t expect the hospital staff to be fluent in English. What is diabetes care like in Tokyo? Are the same type of insulins and technologies used? What if I got so low I wasn’t conscious anymore? What would happen to my mom, who was also in Japan with me? She didn’t know any Japanese! How would she handle this situation? Panic hit me so deep my body started going through tremors, a feeling I’ve never felt before.

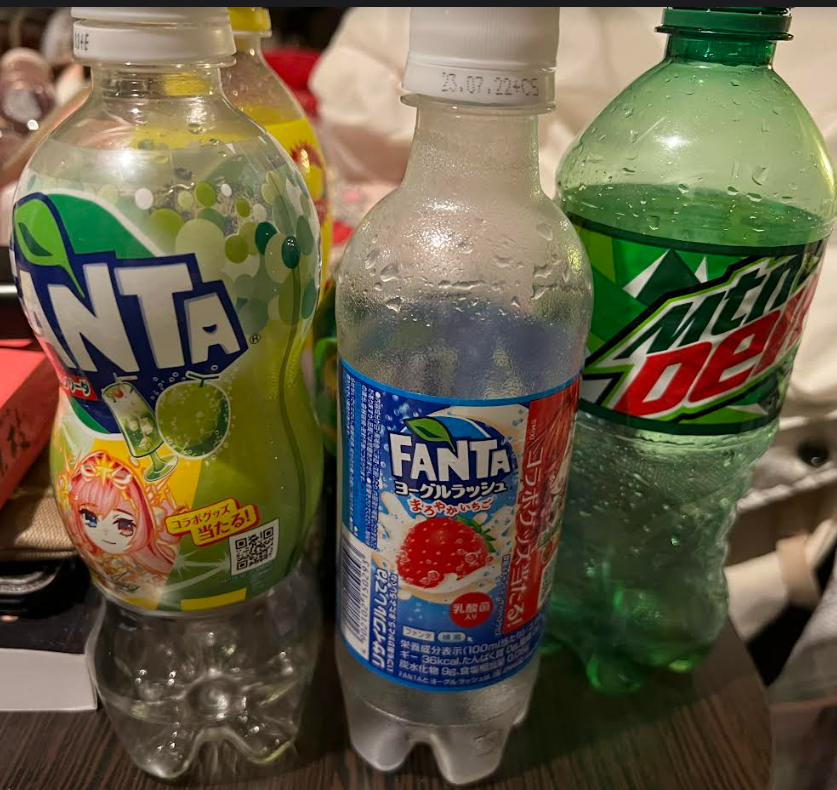

I took every juice I could find and just started drinking. First it was a Mountain Dew. Then it was a Fanta. Then another Fanta. Then a lemonade. Then a Ginger Ale. The blood glucose number wasn’t going up immediately like I wished it was. Half the drinks were ones I still had from the USA, half from Japanese convenience stores, and I had no idea about carbohydrate and sugar contents for many of them. I didn’t care— I was just terrified I would go low. I couldn’t think past the image of potentially being hospitalized in a country where I couldn’t speak the language. Google Translate only went so far.

It’s around 4 AM at this point when my mom and I put on coats and walk to the nearest convenience store. In choppy Japanese, I relay to the attendant, “Watashi wa tonyoobyoo desu. Totemo saato juusu ga arimasu ka?” Google Translate came in handy for additional questions. After gathering a kitchen’s worth of sugary juice based on the advice from the store clerk, my mom and I stood by the corner of the store, waiting for the dredged number to finally go up. Worst case scenario, we weren’t alone. We were in a public place with people around rather than alone in a hotel room.

Luckily, the number did go up. A little too up— at a high of 350, but I felt peace: I could go to sleep without worrying of hypoglycemia. 350 was and is not ideal, but all I could think about was that I wouldn’t go through a severe low. I didn’t have to go to a hospital. I promised myself I’d be careful and never have that happen again.

Well, it happened again, but in reverse. The panic and anxiety of the high blood glucose rapidly decreasing immediately provided a trigger when I ate my late dinner just two days later. It was the night before departing for the USA. My mom and I planned to organize luggages and eat a small meal. I had bought some strawberry cream puffs, chicken, and an onigiri. The food labels were difficult to understand, so I did as many of us diabetics do: we guess in situations like these, based on experiences in the past. What was a blood glucose of 280 prior to my meal went down to 230 within around fifteen minutes of distributing insulin.

Although still a high, what immediately came to my mind was the other night. The tremors fueled by anxiety returned, and I started drinking juice. Again. Except this time, 350 wasn’t the end result, but 516 was. I had administered minor insulin dosages spaced apart to try to tackle the high, but at this point I completely lost faith in my own decision-making. It’s been eleven years of having type one, but at that moment I felt like it was day one. I had never gone through a situation to this extent before, and to have two happen in a short time-span crushed my self-confidence. It felt like the 4,000+ days of me treating diabetes properly from childhood until that moment diminished. I felt like just a “bad” number, dotted on a screen, inflicted by my own incorrect choices. At that moment, I didn’t try to properly conceptualize all the significant changes that I had gone through as a result of traveling. A different time zone with a thirteen hour time difference, a diet that varied from the one at home, days full of over 10,000 steps, and a completely different linguistic environment all made an impact on me as a whole. Looking back now, I realize how these different factors contribute to these situations. It was not a matter of choices or decision-making by itself, but also the natural effect of being in a significant change of environment.

I was fortunate in that my endocrinologist’s office back in the USA was open: Tokyo time was 2 AM during this second incident, but in the USA it was still working hours. I was able to speak with two diabetes nurse educators, who guided me through the process of what to do and told me about classes available for me to take to aid with high stake situations with diabetes. It was one of those moments where I was so grateful for the medical model of disability and the impact those in the medical field have on all of us.

As I write this, it’s the morning after incident #2, as I sit in Haneda Airport. I try to think about what went wrong and all the little decisions that led to the disastrous situations. As scary and terrifying as these two nights were, I’ve realized the meaning of “lifelong” and “chronic” when it comes to conditions like diabetes. Learning happens every day, no matter how many previous days with the condition you’ve already gone through.

The situation also brings up other questions— why is it that in the USA, high sugar, high calorie, and high carbohydrate dense drinks and foods are easy to find? Yet abroad the opposite is true? I saw a similar phenomenon in a previous trip to Ireland as I did in Japan— it was hard to find high sugar drinks as compared to the US! Even without considering a translational barrier in the case of Japan, when scanning labels with Google Translate, a large proportion of drinks were still significantly less sugary than those in the USA.

The most significant learning during these past few days was my realization of how invincibility is only in the films. None of us are invincible, and learning is lifelong. Next time in a Shinjuku convenience store, I’ll be “chuuibukai”— careful. It’s also crucial to understand that for conditions like diabetes, the physical body is not the only place the condition is contained. My two situations were brought about almost entirely by panic, fear, and anxiety. I think it’s these factors that aren’t discussed heavily when it comes to diabetes self-management and care. If anything though, just as important as dosages and carbohydrate counts, it is understanding that the physical and psychological can not be separated. Even more importantly, is learning to be gentle with oneself. During these two situations, I remember feeling like I suddenly lost all my knowledge and education on diabetes self-management. These two situations were just that though. TWO! Two out of hundreds upon hundreds I did successfully work around throughout the years. Changes in diet, time zones, physical activity, language, and culture all have impacts on previous senses of “stability” as well. Invincibility doesn’t exist, but we can try our best every day and learn from all the moments, the highs and the lows.